|

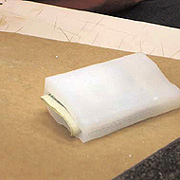

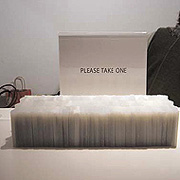

The success of "Cacht"'s process can be measured on many levels. The generosity of the project group and community partnership was particularly productive. The generosity of the attendant and visitor relationship, likewise, was marked with its own kind of generosity. Finally, and perhaps the greatest success in terms of a complex sense of generosity, was a frequent sense of suspicion that surrounded the act of generosity itself. The gallery itself provided materials and man-hours to the production and operation of the project. They constructed a deposit box and slot for the objects and their contents. As well, they actively shuffled and reshuffled the objects in a kind of shell-game to keep the most valuable bills rotating their position. The objects were a hit with visitors and employees alike. Several employees have taken the objects home with them. The front-desk attendants did an exceptional job of assuming the role of impassive distributors of the objects, responding to inquiries using strictly scripted responses. Overall, there was an intense interest and pleasure taken on the part of the community in playing a role in this project. One benefit of the project we did not expect was the sense of engagement it provided between the attendants and visitors. Each of the attendants we spoke with reported great satisfaction over having the opportunity to react to and speak with gallery visitors. They seemed as interested in the characteristics and personalities of the visitors as the visitors were in the art-work. This is a particularly interesting aspect of the project and one with promising potential as a topic of further investigation. It seems that an object in our culture plays a profound role in connecting individuals to each other. Typically in the culture around MIT and Cambridge-Boston individuals assume a public anonymity. Whether there is a desire for interaction with others or not, there must normally be a "reason" or objective for one person to approach and interact with another. Objects, like cigarettes, are usually an effective vehicle for this. What is interesting about an object like that of "Cacht" is that it has no apparent reason. There is a desire for communication on the part of its collectors, but there is, really, no need for communication. An object like that of "Cacht" produces a desire for interaction rather than filling an apparent need for communication. This is a significant role for an artwork in culture: to exist for the sake of no particular need, except to arouse the emotions of curiosity or desire itself. It is particularly the mystery of the object and event—the very absence of a stated purpose—that provides a key function or role for the object. A fallout from this, related perhaps to the norm of public anonymity, is the sense of suspicion aroused by the distribution of the object. The act of unprompted generosity for its own sake is anathema to the codes of public interaction. Several visitors asked if they were being filmed. Some did not believe the attendants when they were told they weren't. In any case, the act of giving seemed to prompt a sense among the people that by accepting the object they were going to be observed. The act of giving seemed to provoke a sense of vulnerability among many visitors. Certainly the context of the gift—in a contemporary art-gallery where behavior is frequently a study of work—contributed to this suspicion. But, I would guess that such suspicion would be prompted in many other contexts. It may be easier to satisfy, such as the assumption of promotion on the part of a store or institution, but it would still most likely be aroused. Again, this would be a useful focus for future projects, especially future implementations of "Cacht." |

|